1. Leasing activity in New York City surged over the summer, driving down inventory and pushing up rents.

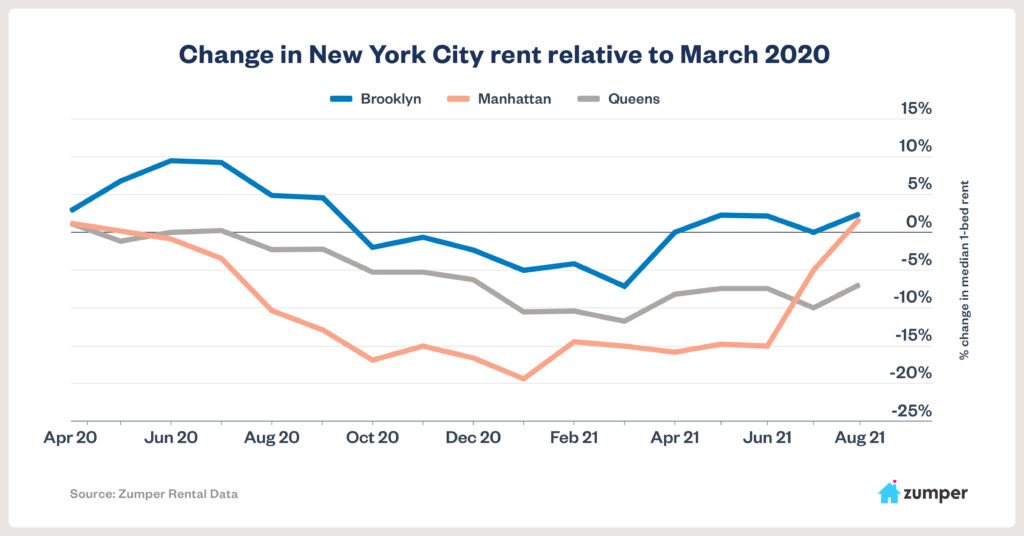

2. After falling 19 percent relative to March 2020, Manhattan rent is now up as wealthy renters return to the city for the fall.

3. Brooklyn rent initially spiked as residents moved in from Manhattan, but trickled down as New Yorkers left the city.

About this report

New York City’s rental market has been the subject of fascination since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. As one of the first American cities hit by the coronavirus, the Big Apple took an early spotlight in the pandemic because of the disturbing images of empty business districts and overwhelmed hospitals caused by the surge of coronavirus cases. The subsequent exodus of residents looking to avoid lockdowns prompted many think pieces in the media proclaiming an end to New York’s appeal.

Of course, the city is now flourishing. While the delta variant has caused a resurgence of COVID cases in NYC, daily cases appear to have plateaued, and the city’s fall events calendar is filled with concerts, comedy, and musicals once again. This has lured back many people who left during the pandemic, as leasing has skyrocketed across the five boroughs over the summer.

The migration to the city has driven rent back to where it was prior to the pandemic, and even pushed New York’s median one-bedroom rent above San Francisco’s for the first time since we started tracking data in 2014. What’s driving New York’s return? Let’s break it down.

How New York rent has evolved over the pandemic

After the pandemic hit, rent went into a free fall as people left and apartment vacancies piled up. In response, landlords offered sweetheart deals to tenants in hopes of filling vacancies in the summer of 2020, with some offering as much as three months of free rent. By January 2021, the median one-bedroom rent was down 17.6 percent relative to March 2020, a stunning drop in such a short period of time in an infamously expensive rental market.

A lot of pandemic housing trends aren’t really new trends, but rather accelerations of pre-existing ones. For example, a young family planning to leave New York when their children reached a certain age might have decided to move during the pandemic. Many retirees who planned to move to Florida in the next few years did so during the pandemic for the same reason.

At the same time, the types of things that bring people to the city—the start of school, an internship, a new job—slowed down because universities were forced into remote learning and offices closed. Add in the acceleration of population outflows to the halt of population inflows, and you have a recipe for decreasing rent.

But after the vaccine rollout began in January 2021, people started to return as restaurants and other urban amenities became more accessible and safer. Over the course of this year, the median one-bedroom rent in NYC has risen by a staggering 19.6 percent. Rent in New York today is now down just 1.4 percent relative to March 2020. The New York Times reported people who got great deals last summer are now subject to dramatic rent hikes if they want to renew their leases.

Manhattan rent swings wildly as wealthy residents move back

Manhattan rent started to drop almost immediately after March 2020. While the predominant media narrative at the time was that people were “fleeing cities for the suburbs,” a more instructive way to look at the exodus is through the prism of class, not urbanism. Wealthy households with the means to move did so because they wanted to escape what at the time was the epicenter of the pandemic. Rent went into free fall in Manhattan, bottoming out in January when it was down by 19.2 percent relative to March 2020, a stunning drop over the course of just eight months.

But the turnaround was even more swift than the fall. For the first six months of 2021, Manhattan’s median one-bedroom rent was down about 15 percent relative to March 2020, but in July it shot up to the point where it was down only 5 percent. Zumper’s August data shows Manhattan is now up 1.9 percent relative to March 2020. Taken together, it took two months for Manhattan to make up a 15 percent deficit.

How did this happen? It’s reasonable to conclude that the same people who caused Manhattan’s drop—wealthy households—are behind its return. With a loaded fall events calendar that features Broadway musicals, the New York Philharmonic, and countless other cultural amenities, it appears the rich have returned just as quickly as they left. With the surge of leasing activity, Manhattan’s vacancy rate has plummeted.

Brooklyn faced a more winding path

While Manhattan rent dropped, stayed flat, and then rose back to where it was, Brooklyn rent was subject to a different migration pattern than Manhattan. This caused its rent to move in a different pattern. After the pandemic hit, rent rose in Brooklyn over the summer of 2020, rising to 9 percent above March 2020 levels. This is because many people who left Manhattan over this period went to Brooklyn, not exclusively to the suburbs as news stories implied.

But a number of headwinds erased Brooklyn’s rent gains by October. While wealthy households in Manhattan were able to leave the city right away, people with less means had to wait for their leases to expire before leaving. As job losses piled up, Brooklynites left the city to move in with family until they found new employment, whether in New York or elsewhere. And as the pandemic dragged on, it gave people more time to decide if they wanted to leave the city as well, particularly young families planning to leave when their children reached a certain age. The pandemic simply sped up that decision.

Brooklyn rent started to rise again in the spring of 2021 and is now up 2.3 percent relative to March 2020. While listing inventory remains elevated in Brooklyn, it’s dwindling fast with the surge of leasing activity.

Midtown office closures keeps rent down in Queens

According to data from Kaiser Systems, New York’s office occupancy rate is lower than all but one city in the country—San Francisco. While that hasn’t prevented rent in some areas from rebounding to where it was prior to the pandemic, that doesn’t mean this trend is universal in New York. The best example of this is Queens. The northwest part of Queens, particularly Long Island City and Astoria, is popular among renters because it provides a short commute to midtown Manhattan, where many offices are located. But with offices remaining mostly closed, Queens rent has been slower to rise than Manhattan and Brooklyn.

While Manhattan rent plunged after the pandemic, Queens’s median one-bedroom rent trickled down and didn’t bottom out until March 2021, when it was down 11.7 percent relative to March 2020. While it’s rebounded some—it’s now down 7 percent relative to March 2020—it appears office closures have prevented more robust rent growth. Like Brooklyn, listing inventory remains elevated but has seen substantial drops during the summer’s leasing surge.

Queens also has more native New Yorkers and immigrants than Manhattan and Brooklyn, meaning those people didn’t leave Queens to return to an origin city if they lost their job in the pandemic, putting downward pressure on rent. They already live in their origin city. Most residents in northwest Queens are New York transplants. Many left during the pandemic, but the added cushion of native New Yorkers likely kept Queens from being as reactive to the same forces that caused Manhattan’s rates to plunge.

Why is New York rebounding but San Francisco isn’t?

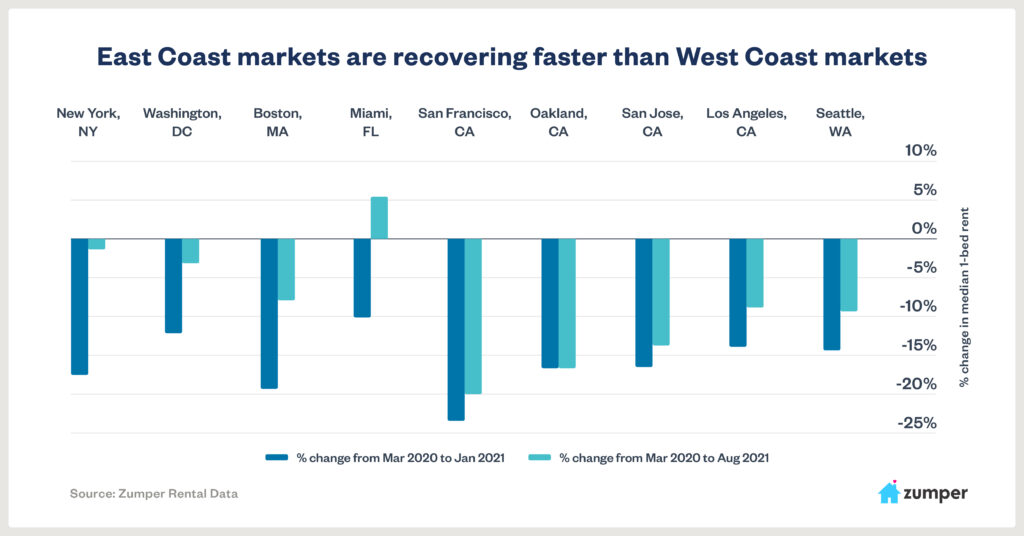

When our August rent report showed New York’s median one-bedroom rent passing San Francisco’s, a lot of media pointed to San Francisco’s exposure to the broad adoption of work-from-home policies as a reason rent has stayed down. While that is true, New York’s office occupancy rate is negligibly higher than San Francisco’s, so why didn’t it stay down, too?

It’s hard to pin down one reason, and it’s likely a combination of a number of factors. It’s still possible that eventual office reopenings push San Francisco rent back up. Most of the city’s residents are transplants, and when their jobs weren’t tied to a location, they left and didn’t come back (yet). New York also has a disproportionate number of transplants, but enough of those transplants stayed or moved back to the city to push rent back to where it was pre-pandemic.

Why New Yorkers moved back despite offices remaining closed is open for debate. It’s possible that New York’s rent drops provided a real price incentive for people to come back, or to move for the first time (work-from-home policies also allowed people to move to the city, not just leave). In San Francisco, rent is down 20 percent relative to March 2020, and still it is just $10 shy of being the most expensive median one-bedroom rent in the country. The price incentive was never truly there because San Francisco was so expensive prior to the pandemic.

New York’s numerous universities might have played a role as well, bringing students back to the city in the summer, when rent snapped back to where it was pre-pandemic. While there are a number of Bay Area universities, the largest ones aren’t within the city limits of San Francisco, and the students don’t live within those limits. Part of the answer could be that more people simply want to live in New York City than San Francisco, regardless of whether their job is based there or not.

It’s also worth noting that the two cities are also exemplary of regional trends. Rent in big cities on the East Coast have either returned to where they were prior to the pandemic or are well on their way to doing so. But on the West Coast, cities have seen rent rise much slower, if at all.